Depression

Approximately 10% of Canadian adults will experience major depression in their lifetime (termed Major Depressive Disorder or MDD). Major Depressive Disorder is a form of mental illness that can affect people of all ages, education, income levels, and cultures. The cause could be due to a complex interplay of personality, environmental, biological, and genetic factors. Major depression is treatable and may involve a combination of different treatments modalities (1). This article focuses on the pharmacotherapeutic treatment of MDD in adults.

Diagnosis

Major depression is not the same as “feeling blue” or “feeling depressed”. Proper diagnosis of major depression requires screening and assessment tools such as the PHQ-9 that are used by health-care professionals (2). The questionnaire corresponds to the symptomatic criteria described in the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition) by the American Psychiatric Association (3).

The following is an excerpt from the DSM-V which are used in the PHQ-9 questionnaire. For the diagnosis of MDD, the first symptoms should include either (1) depressed mood, or (2) loss of interest or pleasure – both are not attributable to other medical conditions.

Table 1: Diagnostic Criteria of Major Depressive Disorder (3,4)

| A. |

Five (or more) of the following symptoms have been present during the same 2-week period and represent a change from previous functioning; at least one of the symptoms is either

|

| B. |

The occurrence of the major depressive episode is not better explained by schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, or other specified or unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders. |

| C. |

The episode is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or to another medical condition.[a][b] |

| D. |

The occurrence of the major depressive episode is not better explained by schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, or other specified or unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders. |

| E. |

There has never been a manic or hypomanic episode. Note: this exclusion does not apply if all of the manic-like or hypomanic-like episodes are substance-induced or are attributable to the physiological effect of another medical condition. |

[a] Criteria A–C represent a major depressive episode.

[b] Responses to a significant loss (e.g., bereavement, financial ruin, losses from a natural disaster, a serious medical illness or disability) may include the feelings of intense sadness, rumination about the loss, insomnia, poor appetite and weight loss noted in Criterion A, which may resemble a depressive episode. Although such symptoms may be understandable or considered appropriate to the loss, the presence of a major depressive episode in addition to the normal response to a significant loss should also be carefully considered. This decision inevitably requires the exercise of clinical judgment based on the individual’s history and the cultural norms for the expression of distress in the context of loss.

Non-pharmacological treatments

Although not the focus of this article, non-pharmacological treatments are psychotherapies focused on personal coping strategies that could be initiated by your counsellor or psychologist. It may be used by your psychotherapist initially to treat milder forms of depression or along with pharmacotherapy. They include Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), Interpersonal Therapy (IPT), Mindfulness Therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Light therapy. (4)

Pharmacological Choices

The goals of therapy for treatment of depression includes achieving remission of depressive symptoms, preventing suicide, restoring optimal functioning and preventing recurrence (4). A clinical guideline for management of adults with Major Depressive Disorder has been published by the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Disorder based on several studies and meta-analyses of available evidence. The recommendations described below are summarized and obtained from the guideline. (5)

How-To Select an Antidepressant (5)

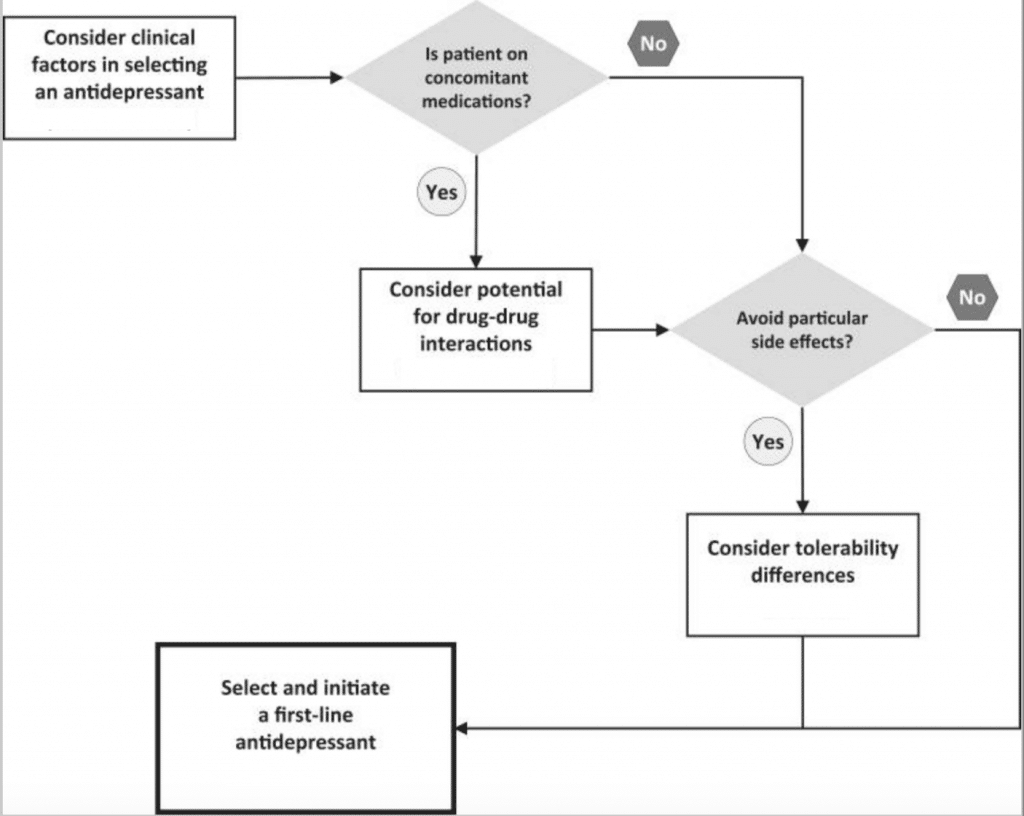

When selecting an antidepressant, the prescriber’s expertise as well as patient perceptions and preferences are taken into consideration. Figure 1 below is an algorithm that summarizes how to select an antidepressant. Antidepressant therapy should be individualized based on the needs of each patient. Some patient factors to consider include:

- Clinical features and dimensions of depression

- Other comorbid conditions

- Patient’s response to previous antidepressants, including side effects

- Preference of the patient

Additionally, medication factors that are considered when selecting an antidepressant include:

- Efficacy compared to other medications

- Potential side-effects

- Drug interactions

- Ease of use of medication

- Availability and cost

Figure 1. Summarized algorithm for selecting an antidepressant (4)

Once patient-specific factors are considered, initiate the therapy from one of the medications among the First Line treatments.

Table 1 below lists the recommended medications in alphabetical order according to Line of treatment from the CANMAT 2016 guidelines. The Lines of treatment are classified according to levels of evidence (i.e. availability of randomized trials) as well as expert opinions of members of the committee (i.e. feasibility of evidence-supported interventions and relevance to clinical practice that considers side effect/safety profile).

Table 1: CANMAT Classification of Antidepressants (3, 4)

|

First-Line Agents[a] |

bupropion (Wellbutrin®) citalopram (Celexa®) desvenlafaxine (Pristiq®) duloxetine (Cymbalta®) escitalopram (Cipralex®) fluoxetine (Prozac®) fluvoxamine (Luvox®) mirtazapine (Remeron®) paroxetine (Paxil®) sertraline (Zoloft®) venlafaxine (Effexor®) vortioxetine (Trintellix®) |

Second-Line Agents[a] |

levomilnacipran (Fetzima®) moclobemide (Manerix®) quetiapine (Seroquel®) trazodone (Desyrel®) tricyclic antidepressants vilazodone (Viibryd®) |

|

Third-Line Agents |

phenelzine (Nardil®) tranylcypromine (Parnate®)

|

[a] Within each category, antidepressants are listed in alphabetical order rather than in order of preference.

Additionally, some studies have shown superiority of certain antidepressants based on head-to-head studies. These medications include: escitalopram, mirtazapine, sertraline and venlafaxine. Although the difference in effect is small (5-6%), it may be clinically relevant for certain individuals when choosing a first-line antidepressant. Table 2 summarizes the superiority of these medications based on meta-analyses.

Table 2. Antidepressants with Evidence for Superior Efficacy Based on Meta-Analyses (5)

|

Antidepressant |

Level of Evidence |

Comparative Medications |

|

Escitalopram |

Level 1 |

Citalopram, duloxetine, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine |

|

Mirtazapine |

Level 1 |

Duloxetine, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine |

|

Sertraline |

Level 1 |

Duloxetine, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine |

|

Venlafaxine |

Level 1 |

Duloxetine, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine |

|

Agomelatine |

Level 2 |

Fluoxetine, sertraline |

|

Citalopram |

Level 2 |

Paroxetine |

Classification of Antidepressants

Table 3 below summarizes the medications according to the CANMAT recommendations, mechanism of action and usual dosage range.

First-Line Agents and Classes of Medications

The following class of medications are the first-choice antidepressants. Within each class, the most common side-effects are described – factors that need to be considered when initiating an antidepressant or switching between medications.

SSRI: Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (4, 5, 6)

SSRI’s that are currently available in Canada include: citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine and sertraline.

Mechanism of Action: Selectively blocks the reuptake of certain serotonin (5-HT) in the presynaptic junctions in the serotonin neurons, resulting in an increased serotonin concentration in the synapse, eventually leading to altered serotonergic transmission.

Common Side-Effects: Side effects mainly affect the Gastrointestinal tract (GI), Central nervous system and sexual function and can be dose-dependent. It can increase the risk of GI bleeding in individuals that are taking other medications which that has the same GI effect (ex: NSAIDs) or have a history of GI bleeding. Nausea is common in this class of antidepressant; which fluvoxamine has the highest propensity to cause nausea. Sexual dysfunction is another issue that could be experienced with SSRI therapy. If this is of a concern and experienced by patients, other options may be more acceptable (e.g. bupropion, mirtazapine). SSRIs are also known to have Discontinuation Syndrome when treatment is discontinued abruptly or tapered-off too quickly (discussed further below).

SNRI: Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (4, 5)

SNRI’s that are commonly prescribed are: venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine. Duloxetine is specifically indicated for neuropathic pain and for pain that is associated with fibromyalgia – which may be considered for patients experiencing depression with any of these underlying conditions. Desvenlafaxine is the active metabolite of venlafaxine – it’s been found to be effective for treatment of depression in peri- and postmenopausal women.

Mechanism of Action: Inhibits reuptake of serotonin (5-HT) similar to SSRIs especially at lower doses, with added norepinephrine blockade at higher doses.

Common Side-Effects: SNRI’s share the common side-effects of SSRI’s, including insomnia, dizziness, somnolence and nausea. Venlafaxine has been shown to have the highest propensity to cause nausea. Sexual dysfunction is also a potential side-effect of this class. Given its mechanism of action, SNRIs can increase the blood pressure at higher doses, which need to be taken in consideration among patients with underlying high blood pressure.

Dual Action Antidepressant (4, 5)

This class of antidepressants include bupropion (Wellbutrin ®) and mirtazapine (Remeron®).

Mechanism of Action:

Bupropion (Wellbutrin®) – although exact mechanism is not known, it is known to act by inhibiting reuptake of norepinephrine and dopamine, increasing the presence of these neurotransmitters in the neuron synapse (classified as Norepinephrine & Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitors – NDRI). It is also indicated for smoking cessation under a different name (Zyban®). It has much less GI disturbance than SSRIs and therefore an option for patients experiencing this side-effect. It is the best treatment alternative for patients taking antidepressants and experiencing sexual dysfunction.

Mirtazapine (Remeron®) – mechanism is not well understood but it’s thought to act on both central noradrenergic and serotonergic systems, increasing their activity (classified as a Noradrenergic/Specific Serotonergic Antidepressant – NaSSA). It has a lower side-effect profile with regards to GI and sexual dysfunction than SSRIs.

Common Side-Effects:

Bupropion (Wellbutrin®) – most commonly experienced are headaches. This medication is generally contraindicated for patients with seizure disorder or recent history of anorexia and bulimia nervosa. As alcohol lowers seizure threshold, patients on bupropion

Mirtazapine (Remeron®) – the most common side effect is sedation, although its somnolent effect is best used in patients experiencing insomnia and depression. Weight gain and dry mouth may also be experienced.

Serotonin Modulators

This class of medication includes the novel antidepressant vortioxetine (Trintellix®) that has been gaining popularity. Another, vilazodone (Viibryd®) has recently been made available in Canada in 2018. Given their novelty, their exact mechanism of action is not yet fully understood.

Mechanism of Action:

Vortioxetine (Trintellix®) – thought to have a combination of direct serotonin modulation and serotonin transporter (SERT) inhibition. It has shown to have positive effects on patient’s neuropsychological performance in multiple cognitive domains when compared to other antidepressants (7). When cognitive dysfunction occurs in conjunction with depressive symptoms, vortioxetine is a viable option.

Vilazodone (Viibryd®) – is a multimodal antidepressant that has serotonin reuptake inhibition and partial agonism of a specific serotoning 5-HT1A. It has to be taken with food to ensure adequate absorption and efficacy and titrated to the target dose.

Common Side-effects: The most common side-effect of vortioxetine is GI-related, with mild-moderate nausea in the first week of treatment. Considering its mechanism of action, it has a lower incidence of emergent sexual dysfunction and sleep disruption compared to the SSRIs. When discontinuing, gradual tapering is recommended down to 10 mg/day for at least 1 week to prevent discontinuation symptoms such as headache, mood swings, vertigo and runny nose.

The most prominent side-effects of vilazodone is GI upset: nausea, diarrhea and also headache.

Second Line and Third Line Agents

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCA): generally reserved as second-line treatment for MDD. TCA’s are generally used as adjunct therapy to 1st line therapy. Amitriptyline is the most frequently prescribed TCA. It is often prescribed at lower doses of 25-50 mg at nighttime for sedation and analgesia. Their use is limited given the tolerability and safety concerns of these medications. Nortriptyline and chlomipramine are other medications within this group.

Antipsychotics: Quetiapine (Seroquel) is a Second Generation antipsychotic agent that has been approved for treatment of depression but considered to be a second line option. Aripiprazole (Abilify ®) has been approved as an adjunct to antidepressants when there is inadequate response to monotherapy antidepressants in adults with MDD. Typically, response to antipsychotic treatment is generally expected within 2 weeks of initiation.

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOI): this group includes irreversible MAOI’s phenelzine, tranylcypromine and moclobemide. They are generally reserved for specialized mood disorder clinics as they require closer monitoring given the associated potentially fatal food and drug interactions (hypertensive crisis, serotonin syndrome). They are classified as 3rd line agents.

Moclobemide is another MAOI but has a reversible property. It does not possess the same dietary restrictions as the irreversible MAOI’s and is generally well tolerated alternative to SSRI or SNRI agents. It is used in patients with a significant anxiety component to their depressive episodes. Given moclobemide’s safety and efficacy profile, it is classified as a 2nd line agent.

Natural Health Products (NHP’s)

Some NHP’s have been evaluated for use as treatment for depression. It is important to note that potential drug interactions can occur with prescription antidepressants and many should be avoided in combination. It is also important to speak to your Pharmacist if you are considering starting any of these alternative therapies or any natural health products to determine if there are any potential drug interactions.

St. John’s Wort: a potential first-line monotherapy option in patients with mild-moderate MDD.

SAM-e (S-adenosylmethionine): a synthetic form of dietary amino acid that may be an alternative second-line monotherapy for treatment of mild-moderate depression.

Omega-3 fatty acids: may be a second-line therapy for treatment of mild-moderate depression, but the evidence for efficacy is lacking

5-HTTP: has been used to improve depression symptoms. 5-HTP is produced in the body from the essential amino acid L-tryptophan. It is then converted to the neurotransmitter serotonin. Taking 5-HTP supplement increases the production of serotonin in the central nervous system.

Table 3. Summary of Antidepressant Recommendations

|

First line (Level 1 Evidence) |

||

|

Antidepressant |

Mechanism |

Usual Dose Range |

|

Bupropion (Wellbutrin®)b |

NDRI |

150-300 mg |

|

Citalopram (Celexa®) |

SSRI |

20-40 mg |

|

Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq®) |

SNRI |

50-100 mg |

|

Duloxetine (Cymbalta®) |

SNRI |

60 mg |

|

Escitalopram (Cipralex®) |

SSRI |

10-20 mg |

|

Fluoxetine (Prozac®) |

SSRI |

20-60 mg |

|

Fluvoxamine (Luvox®) |

SSRI |

100-300 mg |

|

Mirtazapine (Remeron®)c |

α2-Adrenergic agonist; 5-HT2 antagonist |

15-45 mg |

|

Paroxetine (Paxil®)d |

SSRI |

20-50 mg 25-62.5 mg for CR version |

|

Sertraline (Zoloft®) |

SSRI |

50-200 mg |

|

Venlafaxine (Effexor®)e |

SNRI |

75-225 mg |

|

Vortioxetine (Trintellix®)f |

Serotonin reuptake inhibitor; 5-HT1A agonist; 5-HT1B partial agonist; 5-HT1D, 5-HT3A, and 5-HT7 antagonist |

10-20 mg |

|

Second line (Level 1 Evidence) |

||

|

Amitriptyline, clomipramine, and others |

TCA |

Various |

|

Levomilnacipran (Fetzima®)f |

SNRI |

40-120 mg |

|

Moclobemide (Manerix®) |

Reversible inhibitor of MAO-A |

300-600 mg |

|

Quetiapine (Seroquel®)e |

Atypical antipsychotic |

150-300 mg |

|

Selegiline transdermala (Emsam®) |

Irreversible MAO-B inhibitor |

6-12 mg daily transdermal |

|

Trazodone (Desyrel®) |

Serotonin reuptake inhibitor; 5-HT2 antagonist |

150-300 mg |

|

Vilazodone (Viibryd®)f |

Serotonin reuptake inhibitor; 5-HT1A partial agonist |

20-40 mg (titrate from 10 mg) |

|

Third line (Level 1 Evidence) |

||

|

Phenelzine (Nardil®) Tranylcypromine (Parnate®) |

Irreversible MAO inhibitor |

45-90 mg 20-60 mg |

5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin); MAO, monoamine oxidase; NDRI, noradrenaline and dopamine reuptake inhibitor; SNRI, serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

aNot available in Canada.

bAvailable as sustained-release (SR) and extended-release (XL) versions.

cAvailable as rapid-dissolving (RD) version.

dAvailable as controlled-release (CR) version

eAvailable as extended-release (XR) version.

fNewly approved since the 2009 Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines.

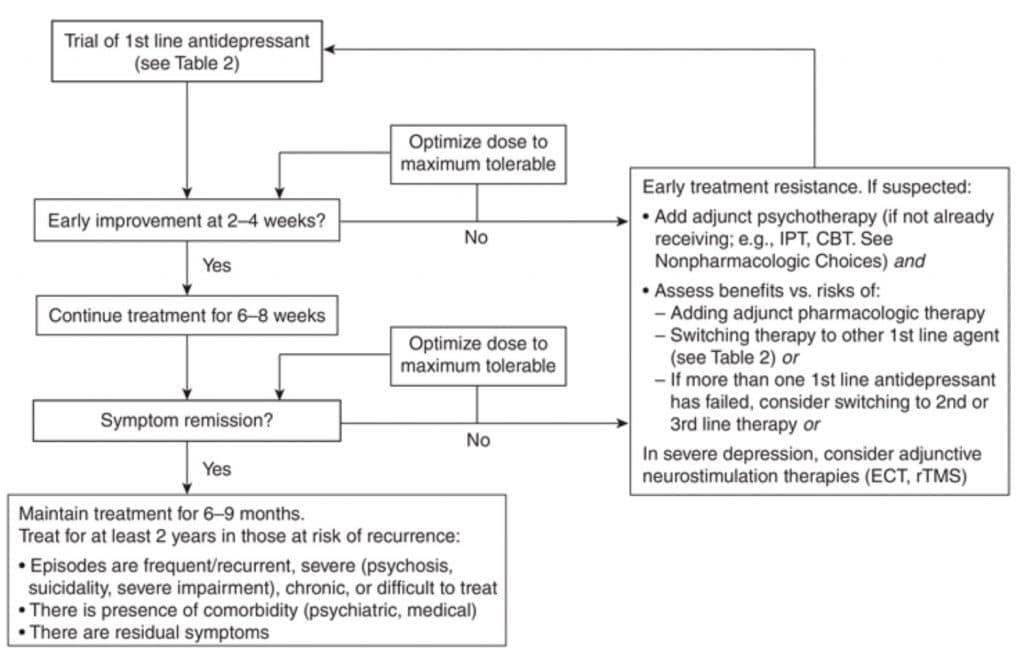

Treatment algorithm (3, 4)

Initiation and duration

Once a first-line antidepressant is selected, efficacy outcome will be assessed in 2-4 weeks using measurement-based questionnaire such as the PHQ-9 or with other symptom score care. If there is only partial reduction in symptoms scores (i.e. 25-49% reduction in score), or there is no response (<25% reduction in score), treatment is optimized by increasing the dose first, while considering a patient’s tolerability. Treatment is then continued for 6-8 weeks and then assessed for symptom resolution. Once achieved, maintenance phase follows.

Considerations for switching to another antidepressant single-therapy (monotherapy) or adding additional medication (adjunct) is discussed further below.

Maintenance and duration

Once remission from depression is achieved, treatment is maintained for a minimum of 6-9 months and then assessed for discontinuation or treatment prolongation. For individuals that are at risk of recurrence of depression, treatment is maintained for at least 2 years. Risk for recurrence include: presence of psychiatric or other comorbidities, residual symptoms, frequent episode or recurrence, or difficult to treat depression. In general, antidepressants should be tapered slowly to minimize risk of discontinuation-emergent symptoms.

The flow chart on Figure 2 summarizes the pharmacological treatment algorithm of Depression (3, 4).

Figure 2. Summary algorithm for management of Major Depressive Disorder

Abbreviations:

CBT = cognitive behavioural therapy

ECT = electroconvulsive therapy

IPT = interpersonal psychotherapy

rTMS = repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation

When to Consider Switching Antidepressant and Adding an Adjunctive Agent

Treatment resistance may be detected if there is failure of improvement after 2-4 weeks of optimal therapeutic dose of an antidepressant. Table 4 contrasts the factors that need to be considered when deciding between switching to another antidepressant monotherapy or adding an adjunct therapy. The decision should be individualized based different clinical factors.

Most clinicians switch out of another class (e.g. from SSRI to SNRI or NDRI) with failure of response to the previous drug. Switching within the same class is also an option, such as when there is positive response with the first medication but hampered by persistent or intolerable side-effects

Augmentation or addition of an adjunctive treatment (combination therapy) can be considered in some circumstances, such as when the 1st antidepressant is tolerated but only partial response is achieved. Adjunct therapy usually involves 2nd line or 3rd line antidepressants as listed on Table 1.

Table 4. Factors to Consider when Switching Antidepressant or Adding Adjunctive Therapy

|

The following are considerations for switching antidepressant: · First antidepressant trial · Poorly tolerated side effects to the initial antidepressant · No clinical response (<25% improvement) to the initial antidepressants · There is more time to wait for a response (less severe, less functional impairment). · Patient preference to switch to another antidepressant |

|

Considerations for an adjunctive medication: · Two or more antidepressant trials done · Initial antidepressant is well tolerated · Only partial response (>25% improvement) to the initial antidepressant · Specific residual symptoms present or side effects to the initial antidepressant that can be targeted · There is less time to wait for a response (more severe, more functional impairment). · Patient prefers to add on another medication. |

aFor the initial antidepressant trial. In subsequent trials, lack of response (<25% improvement) may not be a factor for choosing between switch and adjunctive strategies

Antidepressant Discontinuation Syndrome (8)

More common with SSRI antidepressants than others, is Antidepressant Discontinuation Syndrome which occurs when they are discontinued abruptly, or dose-reduced drastically. The symptoms are summarized by the mnemonic “FINISH”: for Flu-like symptoms, Insomnia, Nausea, Sensory disturbances. These symptoms are not life-threatening but can be bothersome for some patients. The risk is higher if a patient has been taking antidepressant for 6 or more weeks and with medications with shorter half-life (e.g. paroxetine, venlafaxine). Patients could experience these symptoms within 1-7 days of stopping the medication and will subside in 3 weeks if untreated. The syndrome can be reversed if the antidepressant is restarted. Alternatively, when a slow taper is poorly tolerated, a long-acting antidepressant, fluoxetine 10-20 mg could be used as one dose. If emergent discontinuation symptoms are not resolved after a few days, a second dose of fluoxetine could be given. It is therefore important to speak to your care provider if you are thinking of altering your treatment due concerns with your medication therapy.

Antidepressants are tapered gradually by approximately 25% per week while monitoring for emergence of depressive symptoms. Some drugs such as fluoxetine (Prozac®) has a longer half-life and can be tapered more rapidly than other SSRIs.

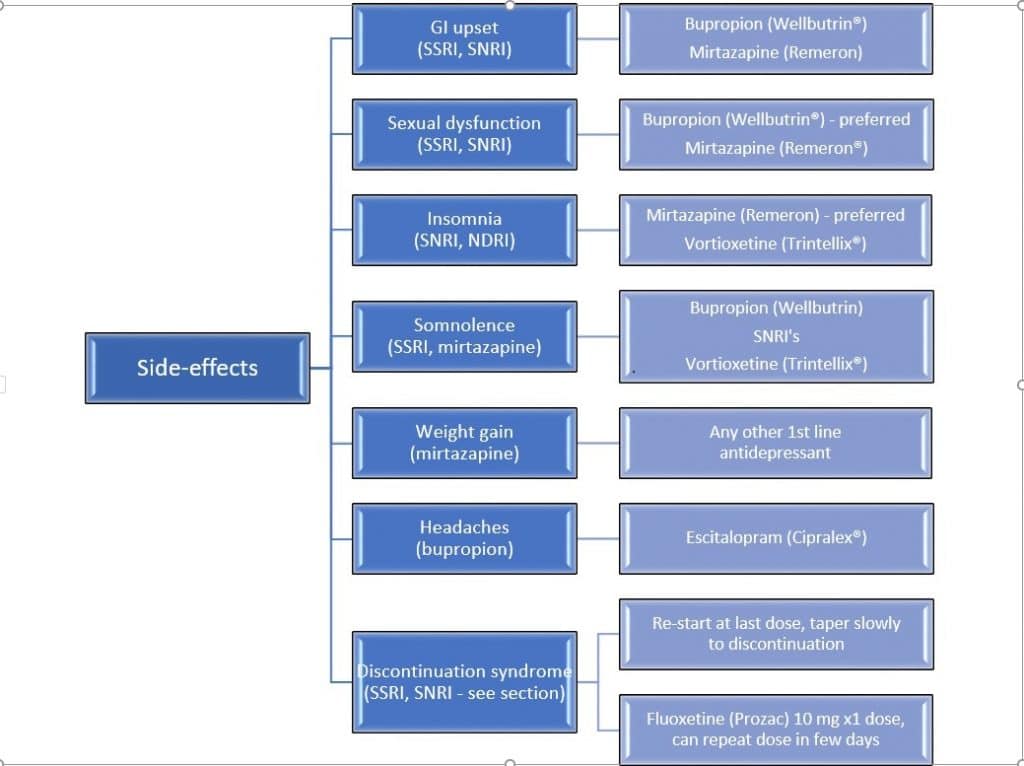

How to Switch Between Medications or Stop Antidepressant

It may be necessary to switch to another medication or class of medication as described in Figure 2, if the side-effects become unsupportable and risk of discontinuation is high. The flow diagram below describes the most common side-effects associated with specific antidepressants or class and the possible options.

Figure 3. Treatment Alternatives According to Side-effects (3, 4, 5, 6)

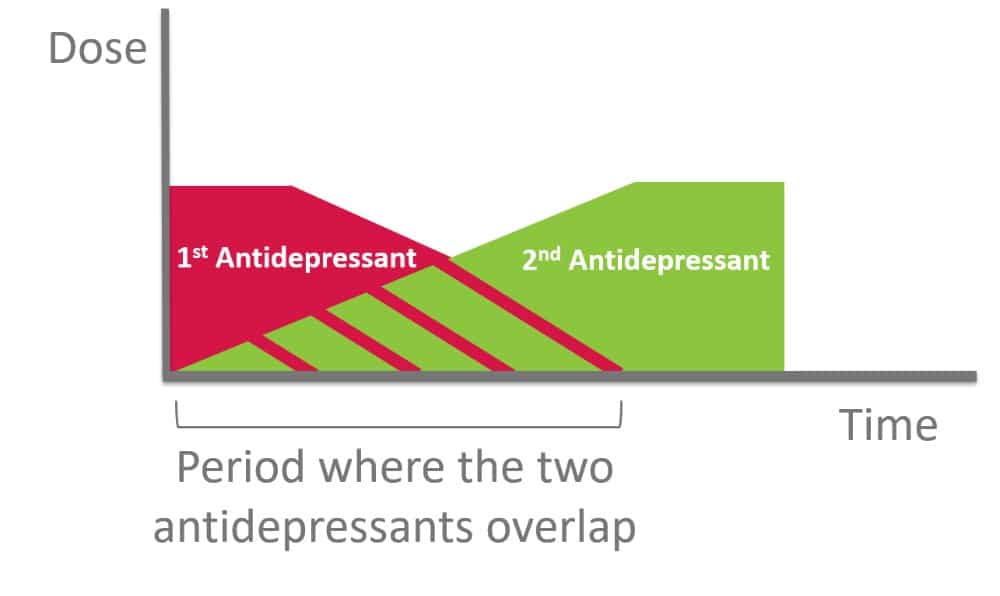

A crossover technique is one popular technique used whereby the previous medication dose is decreased or tapered slowly until discontinuation while starting the other antidepressant at a low dose, then gradually increased. Note that when switching between antidepressants, the principle of dose titration and tapering is applied to minimize adverse effects, in attempt to achieve the desired outcome.

Alternatively, stopping a medication requires tapering to minimize Discontinuation Syndrome. The same dose-tapering principle is applicable without the addition of the new antidepressant. The website www.switchRx.com is a useful tool used by health professionals for switching or discontinuing antidepressants.

Figure 4. Crossover Technique for Switching Antidepressants (4, 10)

Principles of Crossover Switch

- Start new antidepressant at lowest dose possible

- Once new drug is titrated upward to the lowest effective dose, slowly taper the dose of the 1st antidepressant

- Slowly taper over weeks, with flexibility in terms of the

- number of dose reductions,

- size of each dose reduction and

- time between each dose reduction

Information for the patient

In addition to psychotherapy, the following information is important to enhance your antidepressant therapy:

- Take your medication daily

- Speak to your healthcare provider if you have questions about side-effects or other issues

- Remember that it may take 2-4 weeks so experience a noticeable effect from an antidepressant (including dose changes or change in medication)

- Continue to take your medication even if you are feeling better

- Do not stop taking your antidepressant without checking with your prescriber

- Finally, speak to your Pharmacist if you have any questions about medications or supplements.

References

- Canadian Mental Health Association BD. Depression 2013 [Retrieved from: https://cmha.bc.ca/documents/depression-2/].

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depressionseverity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16(9):606-13.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- Kennedy SH et al. Depression. In: CTC [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2019 [updated 2018 May; cited 2019 Sept 20]. Available from: http://www.myrxtx.ca. Also available in paper copy from the publisher.

- Kennedy SH, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, Tourjman SV, Bhat V, Blier P, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder: Section 3. Pharmacological Treatments. Canadian journal of psychiatry Revue canadienne de psychiatrie. 2016;61(9):540-60.

- CPS [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2019 [cited 2019 Sept 20]. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRIs). Available from: http://www.e-therapeutics.ca. Also available in paper copy from the publisher.

- Rosenblat JD, Kakar R, McIntyre RS. The cognitive effects of antidepressants in major depressivedisorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2015;19(2).

- Warner, C., Bobo, W., Warner, C., Reid, S. and Rachal, J. (2006). Antidepressant Discontinuation Syndrome. American Family Physician, [online] 74(3), pp.449-456. Available at: https://www.aafp.org/afp/2006/0801/p449.html [Accessed 26 Sep. 2019].

- Gardner D, Pollmann A. Medicationinfoshare.com. (2019). [online] Available at: http://medicationinfoshare.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/MIS-Stopping-Antidepressants-Feb-20141.pdf [Accessed 26 Sep. 2019].

- ca. (2019). SwitchRx: Switching antidepressants Medications. [online] Available from: https://switchrx.ca/antidepressants [Accessed 26 Sep. 2019].